Some notes I took while taking The Talmud: A Methodological Introduction by Northwestern University on Coursera.

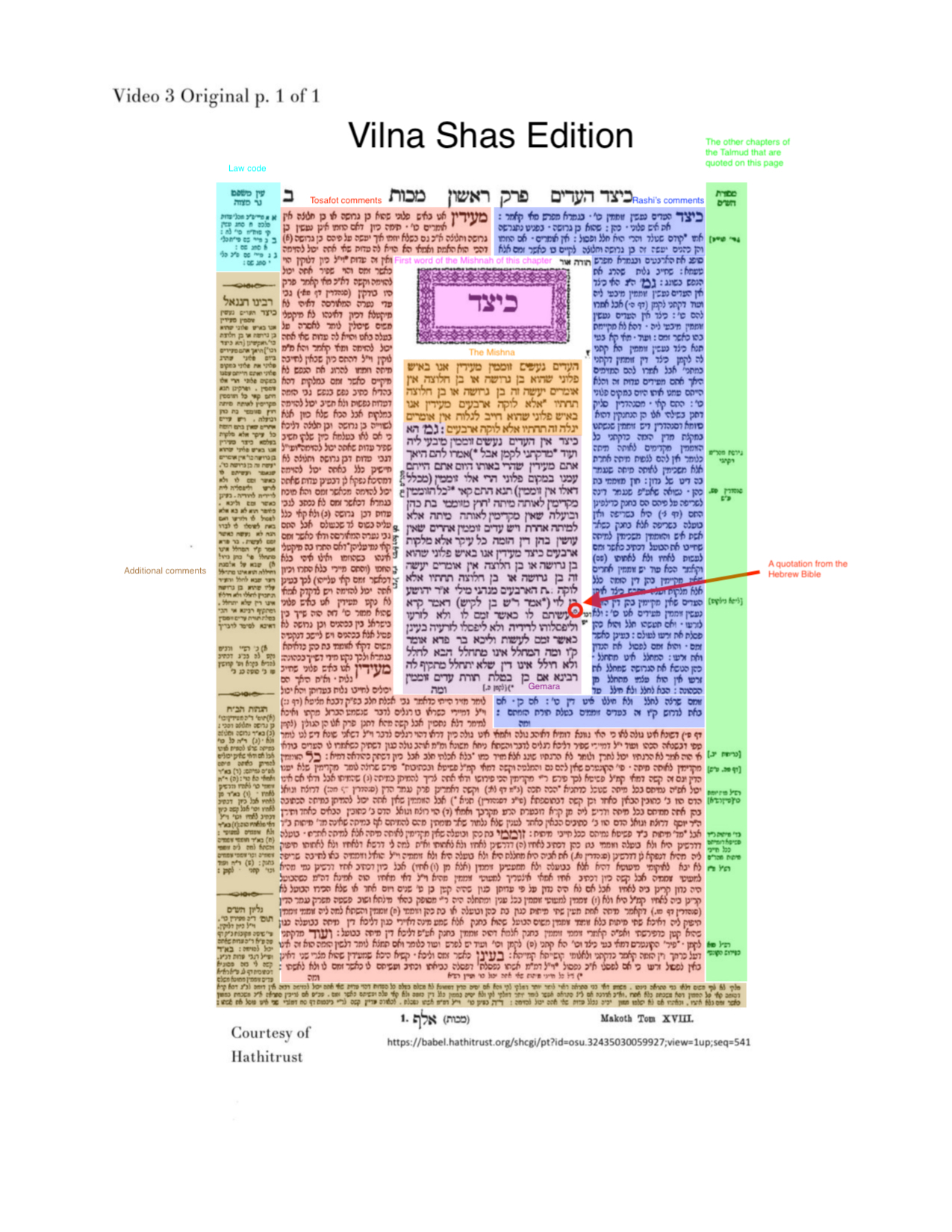

A typical Talmud page:

Week 1 - Introducing the Talmud

The structure of Talmud

Talmud = Mishnah + Gemara

Mishnah = a written compendium of Rabbinic Judaism’s Oral Torah

Gemara = an elucidation of the Mishnah and related Tannaitic writings that often ventures onto other subjects and expounds broadly on the Hebrew Bible

Mishnah vs Talmud

Mishnah

- highly organized

- comprised of six thematic orders which are then sub-divided into subject tractates, or individual volumes.

Talmud

- also composed of orders and tractates

- unlike the Mishnah, the Talmud resists rigid ordering, and prefers free-flowing conversations that range across topics, and then back again

Side note: The six orders of Mishnah

- Zeraim (“Seeds”), dealing with prayer and blessings, tithes and agricultural laws (11 tractates)

- Moed (“Festival”), pertaining to the laws of the Sabbath and the Festivals (12 tractates)

- Nashim (“Women”), concerning marriage and divorce, some forms of oaths and the laws of the nazirite (7 tractates)

- Nezikin (“Damages”), dealing with civil and criminal law, the functioning of the courts and oaths (10 tractates)

- Kodashim (“Holy things”), regarding sacrificial rites, the Temple, and the dietary laws (11 tractates) and

- Tohorot (“Purities”), pertaining to the laws of purity and impurity, including the impurity of the dead, the laws of food purity and bodily purity (12 tractates).

A History of Jerusalem Temple:

- 960 BCE: the first Jerusalem Temple (Solomon’s Temple) was built

- 586 BCE: the Babylonians (Nebuchadnezzar) destroyed the first Jerusalem Temple and exiled the elite population of Jerusalem to Babylonia

- 538 BCE: the Jewish people returned to Jerusalem (set free by Cyrus the Great) and began to rebuild the second Jerusalem Temple

- 516 BCE: the second Jerusalem Temple was built

- 19 BCE: Herod the Great refurbished the second Jerusalem Temple

- 70 CE: the Romans destroyed the second Jerusalem Temple

- Rabbinic Judaism began to develop after the second Jerusalem Temple was destroyed, focusing on religious practices without a temple. The rabbis during this time compiled the oral law from the past several centuries to written law, as the oral scholarship couldn’t continue, and the compilation was the Talmud.

The Major Center of Talmud Study from the 8th-11th Centuries:

- The Geonic Period signifies the five centuries between the consolidation of the Talmud during the 6th century CE and the emerge of the Rishonim authorities in the 11th.

- The Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, also known as the Geonic Academies, was the center for Jewish scholarship and the development of Halakha from roughly 589 to 1038 CE in what is called “Babylonia” in Jewish sources, at the time otherwise known as Asōristān (under the Sasanian Empire) or Iraq (under the Muslim caliphate until the 11th century).

Major European Centers of Talmud Study in the Medieval Period:

- Ashkenaz (now northern France and Germany)

- Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (Rashi = R-SH-Y) produced a commentary on the Talmud that helped its readers encounter the Talmud as a unified and coherent text.

- The Tosafists continued the project of producing the Talmud, as a unified and coherent document.

- Whereas Rashi’s commentary made each chapter function as a unified whole, the Tosafists went a step further and attempted to do this with the entire Talmud.

- Provence (Southern France and Northern Spanish cities)

- Produced significant legal commentaries in the 13th and 14th centuries.

- Nachmanides aka Moses ben Nahman (Ramban = R-M-B-N) and Shlomo ibn Aderet (Rashba = R-SH-B-A).

- Sefarad (Southern Spain and North Africa)

- Moses ben Maimonides (Rambam = R-M-B-M)

Week 2 - False Testimony From Bible to Rabbis

False Testimony in the Bible

Deuteronomy

19:15

One witness is not enough to convict anyone accused of any

crime or offense they may have committed. A matter must be

established by the testimony of two or three witnesses.19:18 - 19:19

… if the witness proves to be a liar, giving false

testimony against a fellow Israelite, then do to the false

witness as that witness intended to do to the other party. …

עֵדוּת (eduth): testimony

עדים זוממים (edim zomemim, edim = witnesses, zomemim = false): witnesses proved to be false

From the word “intended”, the law also punishes someone who only intended to do a crime but hasn’t successfully carried it out.

How the Book of Susanna corresponds to False Testimony in the Bible

| Bible | Book of Susanna |

|---|---|

| in front of the judges and priests | Susanna was brought to a public setting |

| do them as they schemed to do | the two men wanted to kill Susanna, but got killed instead |

| at least two witnesses | two men |

| thorough investigation | examined separately by Daniel |

Mishnah, Midrash and Talmud

There are three genres of literature that discuss what is sometimes called the Oral Law: Mishnah, Midrash, and Talmud.

- Mishnah

- a law code

- organized by topic/chapter

- written in Hebrew in a distinctive, concise style

- Midrash

- a form of biblical interpretation

- shows how the Oral Law can be derived from scriptural verses

- not organized as a code would be organized, typically organized according to the order of the biblical verses

- Talmud

- a combination of Mishnah, Midrash, and many other genres.

- formally structured around the Mishnah

- often asks a question about the Mishnah and answers it with a Midrash

The Structure of Mishnah

If we start reading from the beginning of a chapter, we may think that it seems to be in the middle of something.

That’s because the Talmud does attempts to explain the puzzling features of the Mishnah by seeing it not as introducing a new topic, but as simply a continuation of the discussion of the end of the chapter immediately proceeding it.

Tannaim and Amoraim

Tannaim (plural of Tanna תנאים = reciter): The rabbi’s who existed before the Mishnah and whose opinions are recorded in the Mishnah and elsewhere.

Amoraim (plural of Amora אמוראים = to say): The rabbi’s who were active scholars after the production of the Mishnah and whose opinions are recorded in the Gemara, and other works of rabbinic literature.

The Amoraim perceived themselves as following the Tannaim in multiple senses not just as being chronologically leader, but also as being legally dependent on Tannaitic opinions.

According to Amoraic legal thought, a Tanna may legitimately disagree with a Tanna and an Amora may disagree with an Amora, but an Amora my never directly dispute the statement of a Tanna.

Week 3 - Reading the Bible & Rabbinic Logic

Kal Va-Homer (קל וחומר)

Means “light and heavy”, equal to Fortiori Argument in Latin. It shows what applies in a less important case will certainly apply in a more important one.

Example:

God tells Moses to go speak to Pharaoh and request that he free the Israelites.

Moses replies: If the Israelites, who should be excited to hear that they will be redeemed from slavery in Egypt did not want to listen to me, then by Kal Va-Homer, Pharaoh who will not be excited about his slaves being released will certainly not want to listen to me.

How Do Rabbis Read the Bible?

- Omnisignificance: each word or even part of the word bears meaning.

- Any part of the Bible can be understood in light of other Biblical texts.

- Bible produces deeper meanings when one applies interpretive tools. e.g:

- Kal va-Homer: see above.

- Gezerah Shavah: the existence of the identical word in two separate biblical contexts constructs a bridge between those passages that allows features of the context to travel in both directions.

- Hekesh: a concept between two terms or ideas that appear in close context in the Bible. One’s proximity determines that the analogy exists. One can transfer features of one term to the other.

Note that we should separate the named rabbis from the Talmud’s anonymous narrator.

Week 4 - Redaction & Textual Witnesses

What is a Beraita (בָּרַיְיתָא = outside)

“The Rabbis taught” always indicates that the reader is about to see a statement attributed to a Tana or several Tannaim that does not appear in the Mishnah.

Beraita: a statement attributed to Tannaim that is not in the Mishnah.

How reliable are the Attributions in the Talmud

Scholarly opinions on the question of the reliability of attributions in the Talmud include:

- attributed statements are taken to be useful a source for broader historical claims about different generations of rabbis, but are unlikely to be direct quotes (a consensus middle position)

- attributed statements are presumed to be invented by later editors unless proven otherwise (one extreme approach)

- attributed statements are presumed to be historically accurate unless proven otherwise (another extreme approach)

Editors of Talmud

In the 20th century, scholars realized that the Talmud is not merely a historical record of discussions exactly as they transpired in the study hall, but underwent significant editing.

Evidence of this editing, also called redaction, can be seen in the complex literary structuring of textual units, which could not simply reflect an actual historical dialogue.

Scholars generally identify the anonymous voice of the Talmud known as the Stam or the Stamaim in plural (the editor or editors of the Talmud). The anonymous commentary of the Stam can frame discussions, suggest potential responses to arguments, or attempt to provide explanations of Aramaic statements. The Stam has been characterized both as a harmonizer and as a generator of arguments. At times, the Stam seems to present potentially contradictory statements as part of the same conceptual framework.

Week 5 - Tosefta, Tannaitic Midrash and Palestinian Talmud

Multiple Punishments

Example scenarios:

- Scenario A: Witnesses A&B testify that so-and-so owes $200. If it’s a false witness:

- Sages: $200 and no lashes

- Rabbi Meir: $200 and lashes

- Explanation: Deuteronomy 19 requires a quid pro quo punishment, that is why even the Sages up for $200 overlashes as the preferred punishment. But this unfairly rewards the false witnesses by exempting them from the harsher punishment of lashes, which they have earned by violating the Ten Commandments. Rabbi Meir’s approach ensures that the witnesses get both the quid pro quo and the harsher of the two punishments.

- Scenario B: Witnesses A&B testify that so-and-so violates a ritual prohibition. If it’s a false witness:

- Sages: 40 lashes

- Rabbi Meir: 40 lashes and another 40 lashes

- Explanation: Instead of his statement about the name that brings, Rabbi Meir in Scenario B says that the witnesses received one set of 40 lashes for having violated the prohibition in the Ten Commandments (against testifying falsely) and a second set of 40 lashes in fulfillment of the quid pro quo punishment laid out explicitly at Deuteronomy 19.

Rabbi Meir’s rationale: the name that brings him to corporal punishment is not the one that brings him to compensation.

What is Legal Midrash

Midrash: a rigorous reading of the Hebrew Bible.

A primary principle of rabbinic legal Midrash is the notion that a text has to be marked in some way as requiring interpretation.

- contradictions

- juxtaposition of verses

- redundancies in spelling

13 Principles of Torah Elucidation:

- Binyan Av (construction of a father) https://outorah.org/p/6485:

- A binyan av is a rule derived from a verse (or from two verses) that is applied to all cases that are similar to the one in the verse. Some examples:

- The permission to prepare food on Yom Tov was only stated in regards to Pesach. From a binyan av, we apply this rule to all similar days, i.e., Succos, Shavuos, etc.

- Deuteronomy 19:15 specifies that the testimony of “one witness” is inadmissible. From a binyan av, it is determined that any place the Torah says “witness” without such specification, it refers to testimony in general, which requires two witnesses.

In the Tannaitic period, there was no limit on the number of resolutions that could be offered to add meaning to a marked text.

Our works of Tannaitic Midrash frequently cite the opinions of multiple rabbis who attempt to add elements of meaning to the marked texts. For reasons unknown, leader rabbis began to feel differently about this notion of interpretive pluralism.

Around the turn of the fourth century CE, Babylonian rabbis began to insist that a singular textual marking, redundancy or extraneity, can only produce a single new legal element. And also, importantly, every legal element should be justified through a marked element of the biblical text.

Binyan Av and a Mah Hazad:

One is an analogy produced initially from two cases to one, and the other is an analogy from two cases that emerges from failed single case analogies.

Week 6 - Tosefta, Tannaitic Midrash and Palestinian Talmud

Talmud vs Tosefta

- Mishnah has six topical orders, and each topical order is subdivided into several subject tractates.

- Tosefta (תוספתא = “supplement, addition”): a supplement to the Mishnah, a work that looks a lot like the Mishnah, and is organized on the same paradigm of order, tractate, and chapter.

- Some passages of Tosefta rely syntactically on the text in the Mishnah, making it clear that Tosefta is dependent on, and later than Mishnah. And yet Tosefta is a supplement to Mishnah that preserves material from proto-Mishnahs, that was excluded from Mishnah. That’s because not every idea or opinion that existed among these proto-Mishnahs as oral compilations in the second century was included in the Mishnah.

- For example, the Mishnah imagines a case in which sets of witnesses keep arriving in court to assert that their predecessors are lying. If others came and showed these to be false witnesses, and others came and showed these to be false witnesses:

| Babylonian Talmud | Tosefta |

|---|---|

| “All of the witnesses are killed as liars.” | Divides the groups of witnesses into two sets: {1,3,5, …}, and {2,4,6, …}. “When the Mishnah says that all of the witnesses are killed, it means that all members of one of these groups.” |

Midrash

- There are two kinds of Midrash: legal or halakhic Midrash (aka Tannaitic Midrash), and non-legal or aggadic Midrash.

The two Talmuds (Babylonian and Palestinian)

Similarities:

- Both Talmuds are structured around the Mishnah.

- Both contained comments attributed to rabbis who lived both before and after the period of the Mishnah composition. - Both produced something of a multi-generational conversation.

- Both are marked by intense logic and dialectical analysis and both are written in a combination of Hebrew and Aramaic.

Differences:

- The Babylonian Talmud is much longer in terms of total text, and the average smaller unit, the or is also longer.

- The two Talmuds are written in different dialects of Aramaic.

- While the Babylonian Talmud records attributed statements from six generations of post missionary rabbis, the Palestinian Talmud only attributes statements to four generations of post missionary rabbis.

- The Palestinian Talmud has much less textual signage to facilitate reading.

Rabbis and Romans

The Hellenization of the Jews began during the 4th century BCE. Around the time that Alexander the Great conquered the Near East. The story of Jewish Hellenization is often told as a story of resistance. Jews clung to their traditions and resisted the incursions of Greek philosophy, aesthetics, and athletics.

But the story of the encounter between the Jews and Greco Roman culture is as much a story of attraction as it is one of repulsion.

Greek intellectual life featured a discipline known as rhetoric, in which students were trained as speechmakers or reachers. The rabbi’s who produced rabbinic literature are trained through a tiered curriculum of basic biblical fluency, advanced production of Madreshic and Madraic materials, and at the highest level, Talmudic argumentation. Because of the creativity of rhetoric as a skill, there’s often a fine line between a hypothetical rhetorical argument and complete absurdity.

Week 7 - Narrative and History

Legal Narrative

Talmud contains 2 different types of texts:

- Legal text (Halakhah): Talmudic laws

- Non-legal text (Aggadah): Talmudic stories

A case discussed in Talmud:

There was a certain woman who brought witnesses but they were found to be lying. She brought more witnesses but they were found to be lying. She went and brought a last set of witnesses who were not found to be lying.

Resh Laqish suggests to Rabbi Elazar that this last set of witnesses should not be accepted. Resh Laqish said, she is now legally established as a liar.

Rabbi Elazar disagrees, saying, if she is established as a liar, who established all of Israel as liars?

Scene two opens with an actual version of this case materializing before three rabbis. Resh Laqish, Rabbi Elazar, and their teacher Rabbi Yohanan, the leading rabbi of the Palestinian Talmud. Resh Laqush, again, suggests that the women’s lack of credibility should create a pattern and establish all subsequent witnesses as liars. This time, Rabbi Yohanan responds saying, if she is established as a liar, who established all of Israel as liars?

Hearing their teacher use the same language as Rabbi Elazar had used privately to him, Resh Laqish infers that Rabbi Elazar had heard this position from their teacher and neglected earlier to cite the manner in Rabbi Yohanan’s name. Turning on his colleague, Resh Laqish gives him the evil eye and says you heard this from the iron smith’s son, a nickname for Rabbi Yohanan, and did not cite him? (Therefore implying that Rabbi Elazar was also not credible)

When stories such as this one appear in Talmudic legal context and have significant legal content, they are not ignored by legal interpreters either in the Talmud or after. What these readers generally do is flatten the story into its propositional content. In this case, one would imagine the story as a typical legal debate. Resh Laqish believes you establish a pattern after one brings two sets of false witnesses, and Rabbi Yohanan and Rabbi Elazar believe that you cannot establish such a pattern.

From Sects to Rabbis

It’s said that the rabbis reinvent Judaism in the wake of the destruction of the second Jerusalem temple. However, although the destruction of the temple was an impactful event, there are important ways in which some of the specific religious attitudes and ways of being associated with the rabbis have the roots in the period before the temple was destroyed.

Pre-Rabbinic Judaism was divided into rival groups or sects:

- Pharisees

- Sadducees

- Essenes

- Hemerobaptists

- Jesus Movement

We know several sects of Judaism that emerged during the last three centuries of the second temple period in Palestine and Egypt. Our knowledge of the sects is often based on second-hand descriptions.

Our best source of information about the sects is the Dead Sea scrolls. After this was discovered, we don’t need to completely rely on second-hand resources.

Sect Characteristics:

- intensive religious communities

- employed ideology to distinguish between self and others

- elite social groups

- invested in textualism

- some apocalyptic theology

Sidenotes: Pharisees vs Sadducees

| Pharisees | Sadducees |

|---|---|

| Represented the ordinary people | Represented the priests, aristocrats, and rich merchants |

| Believed all Torah and that Torah needs to be interpreted | Only believed in the first 5 chapters of Torah (Mosaic) |

| Created the oral law | Rejected the oral law |

| Believed in the resurrection | Didn’t believe in the resurrection |

| Against Hellenization | Favored Hellenization |

Parallel Narratives

e.g. the story of Shimon ben Shetah, Judah ben Tabbai, and the false witness.

It first showed up in Mehilta, then the first edition which shifted the roles of the two men showed up in Tosefta and the Palestinian Talmud, then the second edition which added a new ending showed up in the Babylonian Talmud.

The parallel versions of the present story provide a great cautionary tale. Since comparison makes it clear that the story was embellished over time, one would be hard-pressed to accept all but the earliest and most minimal version of the story as history. Beyond the introduction of new facts and scenes, the freedom with which the editors embellished the stories communicate something to us about even the original version of the story. That artfulness plays a role in the production. For the past couple of decades, scholars have been shifting the lenses which they employ from those of historians to those of literary critics. That process has proved very productive as scholars have mined Rabbinic stories for literary rather than historical lessons.

Week 8 - Conclusion

Rabbinic Law as Idealization

Today, scholars use Rabbinic text as sources of broader history skeptically. That’s because the rabbis were a small subset of the Jewish population and that much of what they have to say about life should be understood as an idealistic fantasy rather than a cultural description.

Reception and Impact

The Talmud was disseminated broadly during the Geonic period. The Geonim (plural of Gaon) promoted and distributed the rabbinic version of Judaism throughout the Islamic empire of the Abbasids who ruled from Baghdad.